Text by by David Cross

We are bored when we don’t know what we are waiting for. That we do know, or think we know, is nearly always the expression of our superficiality or inattention. Boredom is the threshold to great deeds.

Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project

Figure 1. Alison Currie and David Cross, De-Limit, 2020, dance work commissioned for 2020, Keir Choreographic Award, performer: Cazna Brass, image credit: Gregory Lorenzutti

De-Limit by Alison Currie and David Cross is a dance work commissioned for the 2020 Keir Choreographic Awards at Dancehouse, Melbourne and Carriageworks, Sydney. A hybrid collaboration between performance maker (Currie) and visual artist (Cross), the work sought to test the premise that a series of functional-perhaps rudimentary- actions played out over twenty minutes, might create the essential conditions by which a small set of ‘dance ‘moments can be brought to light.

Following Walter Benjamin’s assertion that boredom is the threshold to great deeds, De-limit consisted largely of a series of technical actions whereby a solo performer (Cazna Brass) dressed in workers overalls put together an art installation piece by piece. The brightly coloured components including inflatable structures and a pink tarpaulin floor did not have an obvious signification floating somewhere across the languages of abstraction, children’s play centres and a curious sexual fetishism. While the elusiveness of these iteratively revealed objects sustained a degree of interest, their manipulation by the performer could be described as functional, erring towards deadpan.

With the proficiency of a skilled stage technician, the performer manipulated and positioned each component with great skill but with a delicious absence of theatrical flourish or gesticulation. The actions were dextrous but without ‘a stage’ expression and over time, the sense of theatricality-manifest more in the objects than the performance- began to ebb.

Without a complex light plan and with no music, De-Limit felt especially raw, the dance equivalent of a demo tape This stripped-back framing functioned to challenge the space between performance and audience placing greater onus on the objects and their manipulation while not allowing the audience to be shaped or guided by the emotional resonances of a musical soundtrack. This exclusion of conventional visual and aural cues could be seen to expose what was there (assorted objects and performer) to greater evaluation. And for some audience members, the absence of key ingredients rendered the experience stark, mundane and perplexing without any obvious narrative or nuanced drama.

Confronted with a potentially unsatisfying sequence of events and confident that nothing of interest was going to happen, by the ten minute mark the audience was faced with a series of choices. Either, attune their engagement to what was there and keep the frame open, close it down entirely, or operate on a continuum that oscillates between both poles perhaps hoping for a denouement of sorts.

Figure 2. Alison Currie and David Cross, De-Limit (detail), 2020, dance work commissioned for 2020, Keir Choreographic Award, performer: Cazna Brass, image credit: Gregory Lorenzutti

Yet the slow and repetitive tempo of the work was not conceived as an end in itself, or a riposte to dances provisional imperative to entertain, so much as a way of framing dance in a highly specific way. Stated simply, the nineteen minutes of what could be described as a technician bumping in a set, provided the necessary frame through which a small series of counter-actions lasting no more than a minute in total could be inserted into the work. These moments when the performer shifts from labourer to dancer and back again are key to De-Limit for, they speak to the potential beauty of dance appearing unexpectedly and fleetingly out of everyday life. Most of the moments are not strident but unfold almost as uncanny instances: the performer placing her head carefully on a sculptural component; or, arching the entire body over an inflatable form that slowly fills the space underneath her body.

These are not the actions of a technician installing the ‘set’ but someone curiously playing with the objects to see how the body in action might shape their meaning. They are playful ruptures or moments of resistance that push against the repetitive and largely non-creative labour being undertaken. This shift from a state of indifference to a state of active interest speaks to a powerful aspect of dance: namely the imperative to break out; to mess with a system, to lighten the mood and push against the incursion of drudgery. In order that we capture these energies or moments of choreographed play, to draw attention to them, requires that they be framed against restrictive and menial actions. And for these shifts to be credible, most of the experience of the work has to be of the performance of menial labour.

Walter Benjamin’s observation that rather than passing time, one must invite it in, informs this approach (Benjamin, 1927-40, p28). While writing specifically about the nineteenth century Parisian arcades and their re-shaping of modern life, Benjamin was fascinated with the boredom elicited by these architectural structures. Yet his belief that boredom was a prerequisite to the experience of great deeds (something remarkable) offers an important insight into how boredom can serve as a powerful frame from which to draw attention to certain actions, objects or events that stand out from the mundane. Instead of seeing boredom in pejorative terms as wasted time where nothing of value is discernible, Benjamin understood it as a crucial interval that allowed for moments of interest to be clearly and even dramatically circumscribed.

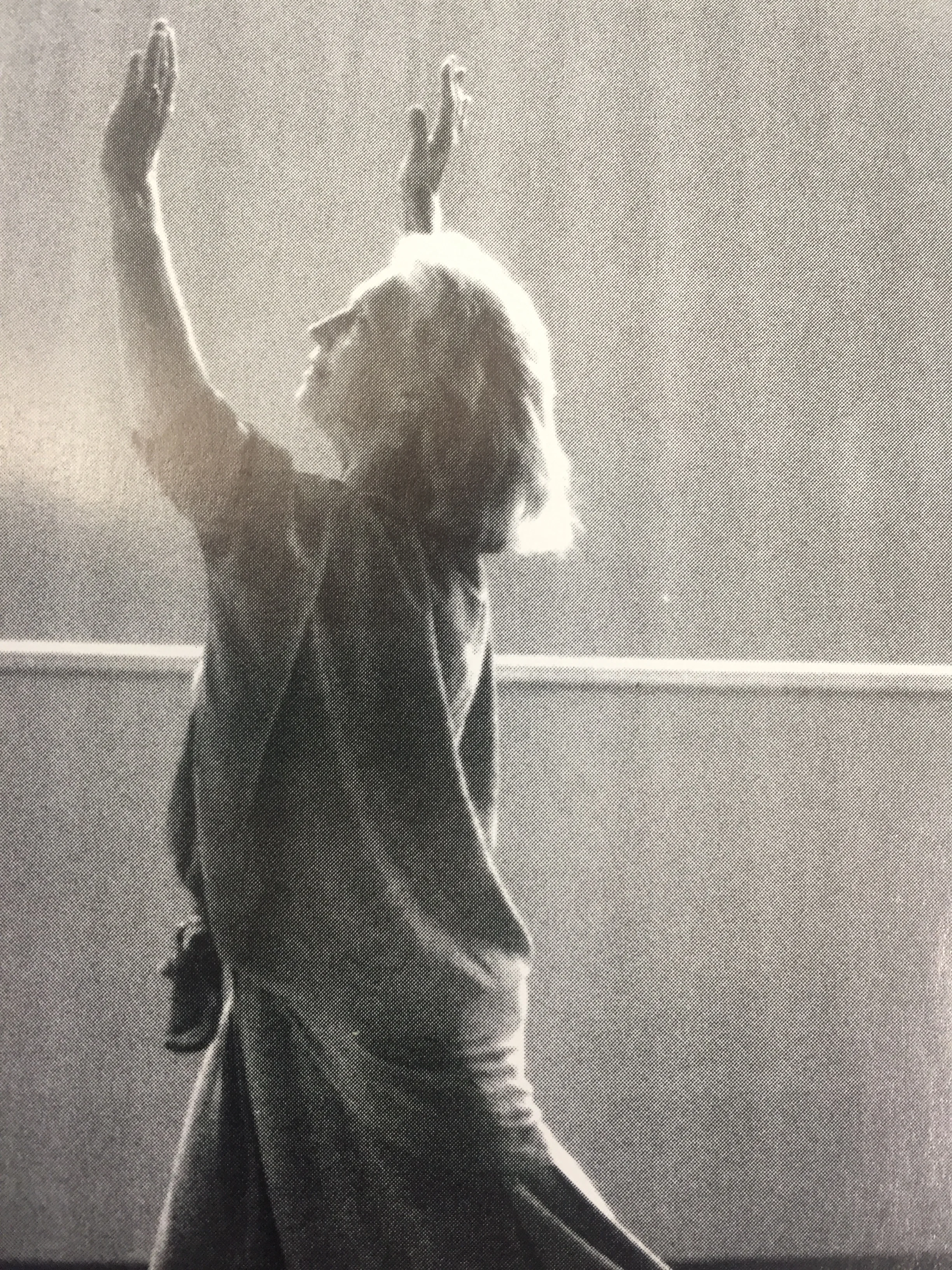

Figure 3. Alison Currie and David Cross, De-Limit (detail), 2020, dance work commissioned for 2020, Keir Choreographic Award, performer: Cazna Brass, image credit: Gregory Lorenzutti

Fundamental to this interrogation is a utilisation of time as a key subject matter of investigation. Specifically, how might the application of a particular temporal register, in this instance a slow, repetitive set of actions over 19 minutes, serve to frame specific moments in different ways? As a broader research question we were seeking to press against spectacular time (constant, multi-sensory experience,) as the fundamental driver of the work and to focus instead on how slow time enables potentially transformatory moments to resonate with increased impact. Heidegger called this approach suspended time, outlining that it captures and demonstrates activities that take place in time but do not lead to the creation of any definitive product (Groys, 2009, n pag)[i].

De-Limit while seeking to play with this idea of suspended time did, however, seek to insert a small sequence in the last ten seconds that called into question the uniformity of suspended time. After the performer completes the installation of the set, she begins to perform what appears to be a different work with a new role. Connecting her body to the set via a Velcro slot in the costume, the performers leg begins to inflate as a yellow structure bursts out from her right ankle.

Just as the assorted objects she had manipulated and tested in the install were inflated one after the other, now the performer had begun to bleed into the work through the action of her costume inflating. This shift from technician to performer is sudden and unexpected. The transformation is further extended when she breaks free from the structure and begins a choreographed dance sequence completely at odds with her previous movements throughout the work. These movements are dynamic, expressive and clearly embody a contemporary ‘dance’ aesthetic. Yet they last for just a few seconds before the work fades to black.

Figure 4. Alison Currie and David Cross, De-Limit (detail), 2020, dance work commissioned for 2020, Keir Choreographic Award, performer: Cazna Brass, image credit: Gregory Lorenzutti

Figure 5. Alison Currie and David Cross, De-Limit (detail), 2020, dance work commissioned for 2020, Keir Choreographic Award, performer: Cazna Brass, image credit: Gregory Lorenzutti

To drill into the territory of boredom is to ask specific things of an audience, not the least of which is patience and a capacity to stay in a work when limited sensory stimulation is taking place. With De-Limit, we specifically invite the audience to engage in their own act of labour -not as an end in itself- but so that they might be rewarded with moments of release when the work shifts its form. Playing with time -especially if it skirts dangerously close to the realm of tedium-is of value we argue for it allows important things (around the relationship between bodies and objects, around repetitive labour, and dexterity) to come into view, to be spot lit and rendered significant.

These things sit in a murky space where dance collapses into everyday life and this territory (while well-trodden) still runs the risk of falling out of an identification with the cultural realm into the world outside the black box or gallery. Yet the riches of the everyday, as countless other artists have attested since the 1960s, are manifold, especially when they can fleetingly elide with the languages of dance to tell us more about how art and life interpolate.

In seeking to understand what precarity might look like within a dance context, especially a competitive context such as the Keir Choreographic awards, De-Limit sought to play with the discourse of task-based performance but specifically to tweak it, to build little blind spots into this system where wonder might briefly, but distinctly, flare from tedium. It gambled that following Benjamin, boredom might be the ballast from which deeds, great or otherwise are brought to light. De-Limit ultimately speaks to the potential of uncanny moments, of using dance to break down the uniformity of a system and highlight the beauty of release.

References

Benjamin, Walter, ‘The Arcades Project’, in McDonough, T (ed), Boredom, Whitechapel, MIT Press, London, Cambridge, 2017

Dezeuze, Anna, Almost Nothing, Observations on precarious practices in contemporary art, Manchester University Press, Manchester, 2017

[1]Groys, Boris, ‘Comrades of Time’, e-flux journal 11, December,2009, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/11/61345/comrades-of-time/

Peter Fischli ‘Sigmar Polke a Contemporary Visionary’ In, Conversation with Mark Godfrey in, McDonough, T, (ed), Boredom, Whitechapel, MIT Press, London, Cambridge, 2017

Lepecki, Andre, Dance, Whitechapel, MIT Press, London, Cambridge, 2012

Spector, Nancy, ‘Time Frame’, in Groom, Amelia (Ed) Time, Whitechapel/MIT Press, London/Cambridge, p130

Acknowledgements

De-Limit was developed by Alison Currie and David Cross and performed by Cazna Brass. Costuming and Design consultancy by Ellie Boekman. De-Limit was commissioned by Carriageworks, Dancehouse and the Keir Foundation for the 2020 Keir Choreographic Award.

DELVING INTO DANCE IS SUPPORTED BY THE VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT THROUGH CREATIVE VICTORIA AND THE AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT THROUGH THE AUSTRALIA COUNCIL, ITS ARTS FUNDING AND ADVISORY BODY. IF YOU ENJOY DELVING INTO DANCE PLEASE CONSIDER LEAVING A CONTRIBUTION. CONTRIBUTE HERE.