Text by Don Asker

Poetics of dancing: exploring the synaesthesia of poetic thought, writing and dancing

INTRODUCTION

It is from a curiosity in creative processes that much of this writing stems. Sharing with others a movement improvisation practice has long been a part of my life. But I appreciate that the term movement improvisation is a rather inadequate description of the time and methods involved in my creative activity, the breadth of which is not readily contained within conventional dance disciplinary boundaries.

Sometimes the very terms used to describe creative practices are inadequate or at best tend to oversimplify what we do. Perhaps this is laziness, but I think it underscores a tendency to not give much thought to the nature of our practice.

I suggest that by loosening the tendency or pressure to identify with one modality it is possible to appreciate the complexity of one’s creative actions. Reflecting upon and deepening our understanding of the processes through which we are creative, places us in a state that by virtue of its non-fixity enables us to evolve more appropriate methods in our practice.

THE SENSES – THE PRIMACY OF PERCEPTION IN CREATIVITY

I’ll step back to reflect on the sensory nature of being. Our sensuousness and capacity to recognize our sensual world was a primal element of our earliest ancestors’ lives. Humans interacted with each other and surrounding lifeforms in what was a very day-to-day, hand to mouth existence. Survival was predicated on sensory awareness. Over time humans have had a significant impact on their surroundings – transforming the world. For many of us today Planet Earth is thought of as a resource to be exploited and developed for human advantage. Our sensory capacities, as with our physical form, continue to evolve and adapt reflecting humans ever-changing needs and activities.

Relationships with other things, entities, country or the landscape take many forms. The growing human population and aggregation in cities have taken humans to a supremely powerful state with the capacity to manipulate and create their environment. Things of a more natural kind are disappearing and not without attracting the concern of some of us. Today around the globe we find movements encouraging walking in ‘nature’, immersion in country or natural environments underscoring the fact that our lives have changed, that we are disconnected from nature. Two hundred years ago the romantic poets walking in the lake country of England were remarking on just this, as they sought to notice and embrace mother nature, a sort of gendered muse, but which also spoke to their perceived need to experience one’s self more sensuously and acknowledge the living world in all its complexity.

Such interest was reflected later by writers like Carlos Castaneda (1969) and David Adams (1997) who examined the details of humans’ engagement in the natural world, a process that Adams aptly called falling under the ‘spell of the sensuous’.

Humans like most life forms have complex sensory systems of touch, smell, vision, hearing, taste and movement all of which are variously active in everyday life. At times we might be consciously attentive, giving primacy to particular sensory capacities as our situation necessitates - we look and listen if we are bird watching, but might shut our eyes as we sit and listen to a music track through our headphones. Often as when we are walking our sense of movement and balance – proprioception – are automatically in play. We have a body memory of doing this activity, we know the feel of walking, and our proprioceptive feedback tells us whether what we are doing fits with that memory and we make necessary corrections (Caldwell, Fuchs, Sheets-Johnson 2012). The human palette of sensory capacity is mostly involuntarily active in everyday life. How often do we think about the way we are walking, standing or in contact with our surroundings? These sensory capacities are more consciously harnessed in particular tasks or activities that require us to develop new skills. Prior knowledge, sensory alertness and purpose can come together in a situation where we are less certain or familiar, where existing templates of behaviour are not adequate. Our sensory system is aroused as we learn, communicate and express ourselves, it helps create personal identities, form relationships, participate in communities and develop our beliefs and understanding of the world.

What is referred to as dancing takes many forms. We learn to dance, acquiring skills in movement, some of which become deeply engrained. Our dance may be attached to or are associated with particular events. Dance thus reflects its context. Dancing for joy or for rain, dancing in a concert, a theatre or a particular site, dancing as a form of self-expression or within particular community contexts all serve a range of purposes. Each dance is structured in ways that respond to and embody the values and purposes of its dancers.

Our own dancing is of its ‘time’; it reflects our selves, and our motivations and our interests. The act of dancing connects us with others as we communicate through a complex resonance. A dance can arouse kinaesthetic responses and stimulate associations and interpretations that may have emotional affect. All this starts very much at a somatic, sensory arousal and can percolate to thought and be articulated verbally.

The cognitive processes of noticing what we are doing or have been doing can be short lived. We don’t always give them much thought, or if we do, it can be but fleeting. We can’t attend to everything, we would be overwhelmed, we are selective. We take our perspective as a complete and unique view but it is shaped by the world-views of our influential peers and community and is bounded by our orientation, values, purpose and attitude in any moment. These contribute to what we sometimes describe as our ‘way’ of seeing things. This might bring a degree of fixity or limitation to our experience. Introducing other processes or enabling our attitude or way of operating to change can refresh, challenge and loosen our particular perspective. We all know the wonder of that as we engage in less familiar modes of creative activity. Feeling less certain and familiar in our creative situation can be accompanied by a sense of risk, feeling less automatic in our doing and with that can come critical reflection and sometimes a search for other options and choices.

Painter Ben Quilty, notes that creative drive requires an enormous self-ego but at the same time he describes having a sense of self-doubt: ‘I don’t know if there is such a thing as a new painting any more’. Working as a painter, he takes the opportunity to examine the world around him with a critical eye. He brings a fresh look at life and the histories of communities and places. He breaks with some painterly techniques and conventions. His work starts to diverge or differentiate from that of his peers. A friction occurs between something ugly and beautiful; an underlying transformation or expansion of a personal aesthetic

Our knowledge grows as experience is more thickly differentiated. Nevertheless, we are in many respects creatures of habit and subject to taking the easiest path. Finding new ways to orienting, or adopting other attitudes or stances is not always the first choice. Familiarity can lead to tacit understanding, not in itself a bad thing, but we are also prone to taking things for granted, and this can crystallise as bias and be experienced as ‘stuckness’.

STRATEGIES FOR DESTABILIZING ONE’S PRACTICE

Perhaps the issue of ‘stuckness’ borne of routine can be addressed by reflecting on one’s methods and noting the patterns. Rather than stop there it is possible to look more peripherally to the irregularities or fringe activities like those time outs, the walks, conversations, the activities that we might marginalise or leave out as of less or no consequence in our practice. We can question the very notion of one’s practice going beyond the notebooks, diagrams, the collections of things, pictures, objects, sounds and physical gestures to consider the details of one’s existence. The potential catalysts for change is within us, but sometimes cannot be recognised in their full significance because we are not open or attuned to the wholeness of our selves.

Our curiosity or passion for something be it investigating a species of beetles, designing houses, re-vegetating degraded sites, or creating artful community events can involve us in activities that sediment into repeated procedures. This can be limiting and backfire as our interest literally isn’t being fed new information or experience. I take some inspiration from an older entomologist friend who went from collecting specimens and making detailed descriptive notes to drawing the animals in their environments. As his process broadened he observed finer details of the animals. He obtained digital images that allowed greater observation of the creatures. His dialogues with other ‘experts’ were complemented by taking laypeople on field walks, where he set about attempting explanations of particular creatures and their habitat, a sort of impromptu postulation and defence of a thesis. Looking more laterally still he saw the broader ecological picture and the implications in many fields including agriculture. At one point he referred to a practice of farming he described as archaic, pre-empting the now quite pervasive push to recognize the values of biodiversity and the risks and dangers of creating monocultures.

Practicing in specific established art forms we can self produce our own specialisation. We risk running out of air and losing ‘touch’ with the many sources that feed, provoke and contextualize our practice. Inevitably it is a balancing act of remaining broadly connected across fields of relevant practice and fostering our individual drive and exploration.

Bringing the focus back to dance, the sense of engagement intensifies when one recognises dance as situated within what I will call an implicit multi-modality of practices. Our dance is nested in many mutually connected creative practices that are available to us and often incorporated without much thought. Our capacity for rhythmicity in spoken utterances, for microtonal aspiration in voice, the ways we intuit tension in sound as well as gesture, the capacity to be spatially aware or move between virtual and live image worlds are all well known to us but often not given the weight and value they might more consciously have as tools for invigorating or refreshing our approach.

Reflect on the ways that the poetics of the moving body proliferate, growing new directions, that wax and wane over time. Think of Taiwanese director and choreographer Lin Hwai-min of Cloud Gate Dance Theatre, Gertrud Bodenwieser founder of the Bodenwieser Ballet in Sydney, and Bangarra’s Stephen Page. Individuals as diverse as Americans Deborah Haye and Trisha Brown and Australians Andrew Morrish and Russel Dumas can become nuclei or inspirational centres for communities of artists rising to prominence, to enjoy levels of local and international popularity.

Lachlan McDowell (2019) in a study of graffiti artists notes that patterns, be they stylistic or formal, regularly emerge and become established and may spread globally through our digital media, but as is the case in other creative disciplines, there will be fresh breakthroughs where further innovations arise. It seems that at points in time the sameness or accumulated style of doing becomes containing and loses its authentic and popular voice in an artistic community. It ceases to have currency and something different is needed. New style arises.

I am not advocating that we attempt lifelong popularity in and through our practices, however, it is worth thinking about the tendency for our practice to become habitual and routine and the implications that this has on our body and creativity. We can become insular and risk-averse and this is not supportive of innovation. Being conscious of this is the first step in rekindling and fostering our creative identities.

In the following rather than consider dance as an insular discipline I examine its interrelationships with intersecting creative processes particularly poetry.

MULTIMODAL PROCESSES AND INTERACTIVITY

Our expressions or activity in dance form can be interactive processes involving others. We might develop a reflexive dialogue where there is an opportunity for mutual witnessing, reflection and responding. In that our practice is the continued exercise of our bodies that have memories, we can differentiate iterations, engage in reflexive thoughts and physically respond in ongoing cycles of action and reflection. We are not necessarily dependent on others as witnesses. Our creative actions can be intrasubjective and the individual artist works to differentiate the present action from the past, the past gesture is resisted and something other required to satisfy the new moment. On the other hand, our collaborative processes, of course, involve the interaction of subjectivities and we might refer to these as intersubjective processes.

Dances and dance more generally can be learned, shared and passed from one person to the next. As we learn a form of dance we absorb its rules, cultural values and sometimes work within these values to interpret or develop our own practice. Our practices often explore degrees of freedom within formal structures such as contact improvisation, where boundaries may include safety considerations, event durations and codes of conduct. In many practices, there is a significant degree of non-verbal communication. We read one another. We respond to others through our bodies and are constantly adapting. The looping or feeding back of experience can occur tacitly and less thoughtfully in each moment of our practice – our choices made quickly from within the learned and practiced framework ‘holding’ our options, or be given more conscious thought and analysis over time as we find reflective opportunity. Of course, we often talk and are constantly thinking and our responses range widely.

The embodied dancing experience of some individuals may be accompanied by other creative activity including poetic writing, visual depictions and sound constructions. American Remy Charlip combined design, drawings and poetry, Melbourne based artist Greg Dyson works in crayon sketches, music and sound constructions and Jane Mortiss makes drawings of dreams, sculptures of birds, and writes poetically about the landscape. In fact, the creative process is often a mix of explorative processes giving form in many modes. The created materials and ephemeral forms of dance can share generative nodes with other modes of expressive and creative activity. In collaborative contexts, they reflect the subjectivities of the participants and in their different modes ‘inform’ on underlying drivers, provocations and aesthetic values. Cage and Cunningham in the 20th century, are a well-known example of the capacity to collaborate and situate their particular disciplinary skills in a larger frame of interactivity and creativity. Tim Etchells, writer, visual and performance artist and director of experimental performance group Forced Entertainment works across a wide field and different mediums, often collaborating with others to generate projects that have the capacity to unsettle and provoke audiences.

At the centre of many of my projects there is a fascination with rules and systems in language and in culture, in particular with the way these systems can be both productive and constraining

Recognising the underlying motivations of one’s creativity and awareness of the potential of diverse modal forms to contribute to the creative process are central elements of the artistic practices mentioned above.

In the diverse settings in which dance manifests, we find practices that are a complex intertwining and reflexivity of expressive forms. For instance, in many therapeutic contexts, dance, stream of consciousness speaking and reflective dialogue can be present in fostering wellbeing. Interestingly the benefits of moving and poetic expression in dance can be felt but it is in the verbal articulation, the naming as it were, that further insights can arise. It doesn’t mean words are dominant, simply that they are part of processes in which dance occurs, is made and understood.

We are part of an everchanging environment. Global concerns with fire, flood, food shortages and vulnerability to new viruses are some of the more obvious indications of our interaction and embedded situation. Importantly we draw on past experience, stories and metaphors as we make sense of our day to day lives.

Today there is considerable research into the ways that action, thought and language are associated. See Body, Metaphor and Movement (2012) where Thomas Fuchs describes tacit memory and its embodiment and the kinaesthetic aspect of memory is articulated by Maxine Sheets Johnston. We are beginning to appreciate that practical knowledge is stored in ways that bypass language.

MEANING, METAPHOR AND GESTURE

Dance can be an abstraction of lived experience, bypassing practicalities to point towards philosophical, ecological, spiritual or ontological questions and subjects. It can give form to emotional feeling or reflect social and civil values. It might remark or draw upon everyday acts and situations, and quotidian reflection seems to provoke artists like Susan Rethorst (2012) and Sandra Parker.

I’ll keep the focus for the moment on dancing that involves the body. It is regulated by community values. It has a long history of gatekeepers whether that be through the control exerted by philanthropists, government funding agencies, or community approval and support. We find that artists continue to explore at the edges of a conservative society, and their work can challenge our beliefs through its representations. In some respects, art is a thesis, a proposition for us to reflect on. It has agency.

We do need to be mindful that insights, critical thinking and analysis of movement-based creative practices reflect the values and frames of reference of the writer and much of the dance literature and commentary in the past has western origins. I want to emphasise that all dancing arises out of a cultural place; it has been formed and enacted within the complex interactions of individual and community values and beliefs. It comes with its own cultural DNA and is of its time. There are inevitably implicit codes or formal parameters surrounding and informing the dance. In my case, I am interested in exploring ordinary action for its physical detail and the revelations that might flow from this process. There is a loosening of action from intention at times, a sort of messiness, and this can lead to a sense of abstraction that might bring me towards understanding the action differently. The process disconnects or releases me and sometimes the witness from gravitating to a particular interpretation. Although we might see this as simply abstracting, it is in some respects, as an archaeology of movement and supports both imaginative engagements as it allows for appreciating the fleshly located experience in all its sensuous spectrum.

It is more complex than an abstraction of behaviour. The practice allows for patterns to be disturbed, for associations and re-interpretations and brings recognition and revitalisation to everyday life. As was noticed by Lakhof and Johnson (1980), a fundamental mechanism of mind is the capacity to draw on our lived experiences, actions, thoughts and behaviours and create metaphors in language to understand things that are less familiar. Metaphors significantly shape the way we think and act, bringing to consciousness more innate aspects of daily lives. I am curious as to the possibility of my gestural abstractions reflecting bodily understandings; aspects of my identity that lie at the periphery of my fleshly engagement that is in many ways so regulated and culturally determined.

THE METAPHORS OF POETRY

Poetry is differently regulated, indeed has flexibility of form that is not bound by linear narratives. Poetry can create space for imaginative engagement, employ fragments of feelings, use images in non-linear structures, frame questions, voice uncertainty, and contemplate chaotic circumstances. Poetry often engages us in our own ruminations and interpretations. Sometimes poetry fosters questions rather than coherence, provocations for thoughtful consideration rather than explicit answers and can touch us through sensual means.

Several decades ago, Laurel Richardson (1994, 2005) described the inflexibility of current academic writing and her perception that creative writing was marginalised. Her ethnographic studies using poetic form highlighted the potential of creative writing and use of metaphor in describing and understanding experience. Imaginative freedom can pay dividends as thoughts leapfrog in free associations, part of mental activity we might refer to as streams of consciousness. Lived experience can be extended into fictional realms and the subjectivity of reality can mean the crossing from reality to fiction is blurred. The act of crossing, however, can lend some definition to either side

In seeking to make sense of poetic writing we become more active participants with the word. Phrases can be spring planks for interpretative acts. In parallel ways we may involuntarily resonate with the actions of others, we experience the same motor neuron firings, and have a feeling of moving or kinaesthesia connecting us to the other who is actually in motion.

There can be a bodily recognition of action and we may place this in all sorts of imaginative contexts or remembered experiences. As writers know we may return to familiar tropes, gravitate to certain themes, and be drawn to particular associations or metaphors. Other artists including movement-based creatives know how quickly we build motifs and develop lexicons. We know more about the tendency for aspects of our practices to be unhelpfully consolidated and limited as themes become patterns in our work and methods. This is not to say that choosing to focus is a bad thing at all - it is when this happens tacitly – without us being aware - that we may lose out.

In a long-term collaboration with Jane Mortiss, I improvised physically and wrote in loose prose or poetic form. We found we sometimes lassoed from events of our lives and worked imaginatively such that not only were we fictionalizing our identities, but we were able to elaborate our beliefs and deepen our understandings of each other. I think we redefined notions that had been central in our individual practices.

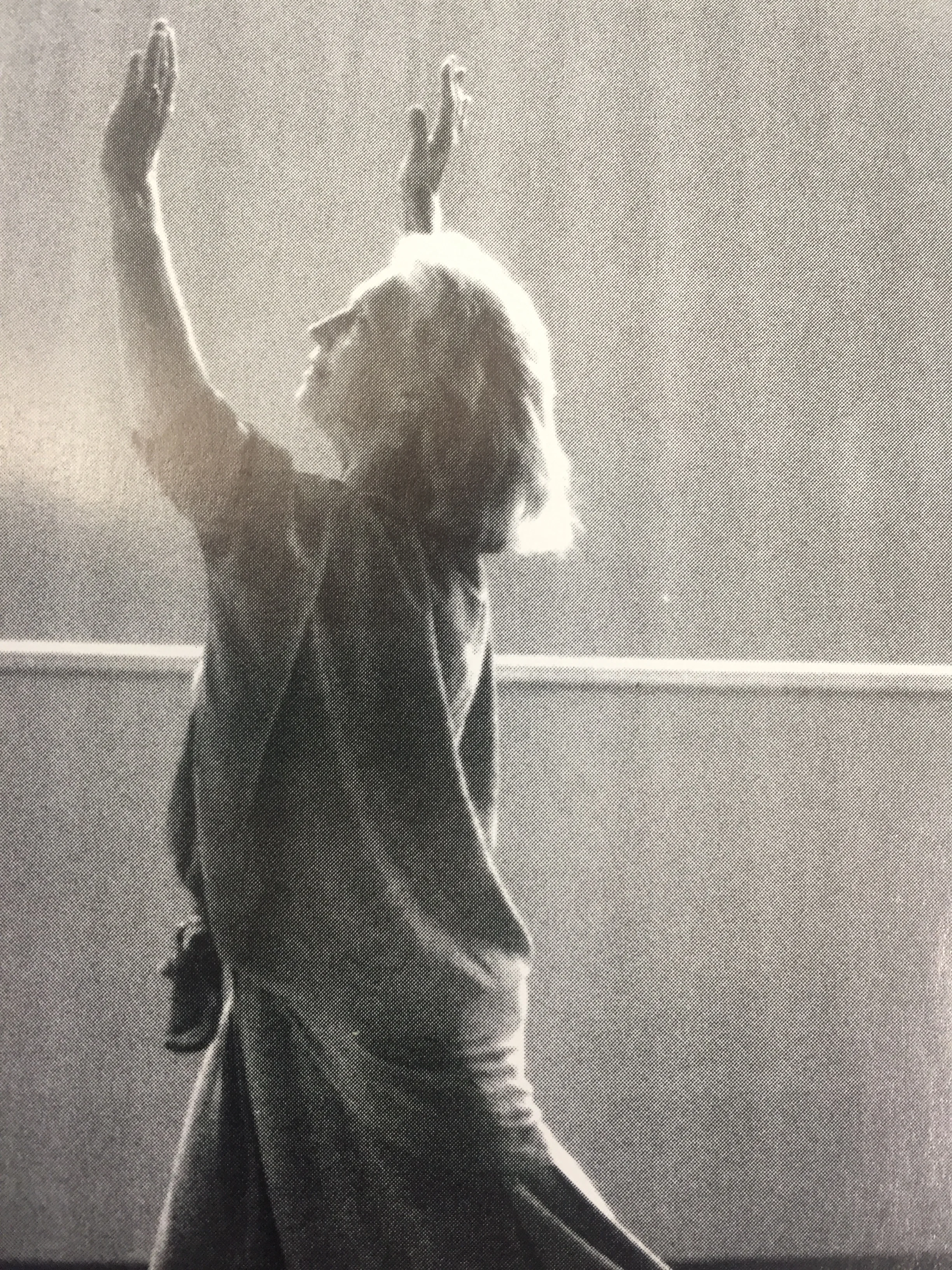

The two poems below are from a collection Dear Heart, I made during that period (2018-2020). The movement images are drawn from Jane’s performative assemblage Divergent Dancing (2018), but first originated in those early improvisations.

Embodiment

The dust on the wall

Marks her clothes

A reminder that we can’t delete what’s been, not ever.

Universally occurring

The substance of us

Lived tenuously in the arc of dust to dust

Not just a life

Separate and contained

But itinerant matter without borders

A thorn under the skin,

Conflicted materials

Ruptured gland becomes fluid between-ness

A parasitic attack,

Drug overdose

A chemical assault on a body of organs

A bottle of gin

Made light work of

Reflect the relativity of hosts and parasites

The remade body

A prosthetic hip

The alchemist’s delight as metal meets biology

Systems within systems

Life has no frontier

Rather degrees of contagion

The trace of cologne

Or damp skin on the wall

The clump of grass that turns the dog’s nose

For a second we linger

Recognisably so

Before complexly dissolving in a bigger palette

Flying

High above the eucalypt ridge

A sea eagle, one of your favourites

Battling two currawongs

And a strong sou-westerly

Sharply banking and bursts of flapping

A young bird by its mottled plumes

Getting a lesson for transgression

Interloper dispatched across the river

The black pair flip-flop down

Disappearing

Into the canopy

Silent shadows again

The capacity to soar catches your attention

Flying is part of your dreamscapes

Effortlessly gliding above the plains

Or hovering inside spacious rooms

Leaves you almost speechless

Next morning

You seem to feel the action

Of the body’s soaring

Know the vistas and the ease

That riding thermals or gales might bring

The remarkable lightness of being

Perhaps kindled in the thought of not being

Like this tiny bird in your hand

A few grams only

With plumage of exquisite colour and form

Wings skilfully articulated

For aerial manoeuvres

That can surprise a fly

A reminder of the fluidity of our environment

Of the means of movement

Of the intricacies of living muscle and shape

And how little is needed

THE EMERGENCE TO CONSCIOUSNESS OF METAPHORS

In therapeutic practice there are parallels between implicit body metaphor and linguistic expression in metaphor. Kolter et al. describe a session with a patient who begins to articulate her understanding of repeated swinging of her arms as life is full of ups and downs. They suggest there is a progression between ‘implicit body memory to explicit declarative memory’ (2012: 210). There is inevitably continuous shaping or affect upon the process by the emergence to consciousness of metaphor.

Explicit memory is expressed not only in speech but also in gesture. Kolter uses the term ‘sleeping’ metaphors for those patterns that exist in the body but that are not consciously referenced and reflected upon.

It is not an aim within my creative practice to form and polish metaphor as such. Rather it is that metaphor can be a tool in processes of making sense of our lives or parts of experience. Metaphors have degrees of ambiguity that provoke a questioning attitude, they can be pointers to areas or subjects that we become interested in understanding in the course of our embodied practice(s).

They can house the complexity of that which is not fully known, allowing for and acknowledging uncertainty, interpretation and approximation.

Recognising that dance - the poetics of moving - and poetry that takes written form, can be housings for metaphor is tantamount to giving permission to gesture’s ambiguity, to the complexity of ourselves and to the approximations of our attempts at truths. Paradoxically in working with a palette of different modalities comes a means of focusing or ‘depthing’ our ‘sense making’.

HEIGHTENING PERCEPTION AND CHANGING PERSPECTIVE AS PROCESS

A practice of working creatively and reflectively in both poetic writing and bodily forms is what I am most focused on here. These two creative modalities have been my central methodological processes in recent time. Movement improvisation within different spaces is an almost daily occurrence accompanied by less easily qualified reflection. If witnesses are present conversation, reflection and response flows in relatively unstructured ways, including cycles of intersubjective responses in non-verbal and multimodal forms. The processes of poetic writing can occur in different times and places.

Every part of these processes is linked to daily life and broader cultural interactions. The infinitely increasing and continuous ways that we know each other and our world means that we are drawn into deeper debates and considerations of human experience as Geertz insightfully asserted as he considered the ways and means of interpreting cultures (1973).

The tacit knowing acquired through experience is something we draw on every second of our lives without consideration. Our actions in the world can become second nature. For example, I know that I must walk carefully in a particular wetland, the ground is uneven and there are wild creatures that I need be careful of disturbing. After many years traipsing in this area I find myself managing to be there safely without giving safety much thought.

In reconsidering the way I am perceptive, my sensory articulation and orientation and attentional emphasis, it is possible to appreciate more details of my experience and what I am connecting with. It’s like putting on prescription glasses when one has been making do with less effective vision. There can be surprising clarity. Furthermore, the full gamut of our sensing apparatus can be brought to consideration broadening our somatic experience. My walking on the wetlands might tend be more consciously visually or audibly alert, but periodically I can feel this switch to include smell or my own movement awareness. I might then be cognisant of the small undulations of the ground, its cracking and curling in the summer, the spacing of tussocks requiring me to dodge or zigzag my course, the smell of the damper ground in more shadowed sections where gullies run into the surrounding hillside. For this to happen I need to be provoked, for example, surprised by unusual numbers of red-bellied black snakes in the landscape or actually change my attitude or bearing from within. The latter seems accompanied by adopting a less certain stance and being open – a state of heightened arousal - and curious.

In recent projects involving longer and more attentive inhabitation of sites the capacity to engage more multi-sensorially has contributed to the detail and thickness of my observation and variation in approach. In making such shifts I notice my automatic or patterned behaviours and start to know myself (Asker 2018, 2019). My experience suggests we can engage in transformative somatic practices and other re-educative processes ‘that can free the lived body from its current shaping and reshape it anew’ (Behnke 2010: 232).

There is another perspective on self-development, one that borrows from autopoietic theory, which refers to the capacity of an entity to reproduce itself.

Autopoiesis, when applied to writing, can be the tendency of the writing to return to a particular idea. It is recursive and we might see this as a limitation. What was propounded by Maturana and Varela (1981: 7) in a biological setting has been extended to social systems with the argument that the system is able to repeat itself or generate its components, and that this occurs through and is observable in its communications (Luhman 1995, 2012).

In the academy of the arts, we can point to practices that are both the heritage of creative disciplines and also the fundamentals for creative developments in the future. Lineages of artist practitioners are reflected in both the underpinnings and conservative elements as much as they are the genome of creativity and innovation. In that, an academy can choose with whom and how it communicates lies the potential for its development. The proliferation of academic exchange worldwide is an indicator of how this valued. Processes of observation of other academies can reveal synergies or differences in philosophical approach, in methods and practices and allow not only benchmarking but provide useful perspectives and foster future partnerships.

Individual artists or creative agents have long reflected in their choices to collaborate or co-produce, an innate awareness of the value of interaction and implicitly communication with others. Being mindful of one’s capacity as creative agent to go on reproducing work in a particular or idiosyncratic way, the idea of extending or diverging is sometimes reflected in the artist seeking to change aspects of the practice. It can be a change of cultural environment, a residency elsewhere, the exploration of less familiar materials, different purposes, new partnerships and collaborations. We need to bear in mind that as we compare or differentiate systems that foster creative practices we tend to do so in terms of the values of our own system.

Within our practice, we cultivate selected attributes and look for signs of these in other parallel settings or practices. We are pre-programmed to seek information and our judgements reflect that. I value risk and uncertainty as ingredients of live performance. I am aware this predisposes me to carry unjustifiable expectations to other works that might aspire to more conservative or historical objectives.

Crossing disciplines can be the opportunity to experience new playing fields. We might move to new mediums, as for example dancer, choreographer Sue Healey has done across decades as she explored the moving image to create sensual kinetic video portraits that can be installed in gallery spaces. Her work On View: Thinking bodies dancing minds (2018) is a good example. Crossing enables us to know the form of things. It brings us into contact with the other side, and we know shape and form. It involves perceptual change, viewpoints are differentiated and can lead to value change - the principles that govern our aesthetic and moral action. It can be a cognisant step – we know what we are leaving and the dimensions of the thing we are entering, such as a move from classical theatre to applied performance, contemplation and exploration of new ways for engaging performer and audience, or consideration of the creative process in community contexts as having other purposes than the performance goal. These are steps or movements from the locus of existing practice in a field to something else. Steps that take time, have duration and render what was as lived history.

Changes are not only of a practical kind but involve new patterns of thought where perceptual adjustments accompany shifts in intention, purpose, orientation, and action. From the subjective aspect, meaning, the making sense of experience, has a changing lens over time. Individual cognitive processing with its basis in a self-referential frame is never completely isolated and can be a fertile medium for change.

Those of us who have hit the wall of ‘stuckness’ (Lett 2011), experienced critical periods of dissatisfaction or a sense of disconnect know the importance of taking stock and re-purposing our lives. Such times are an opportunity to reflect on what is significant in our practice and to what and how we direct our attention? We can fundamentally explore our sensory system and be receptive to other perspectives. We might view our practice in more analytical terms thinking of ourselves as complex systems interacting with everchanging environments and consider how and in what ways these various aspects of our experience are affective. At the heart of this process, lies acceptance of a state of uncertainty, in the spaces of which we find opportunity to make sense of our experience. We might ask have we imposed unreasonable or impractical boundaries on our practice? Are we flexible in our approach and able to find other perspectives? Does our connection with others, our communications and the sites and situation of our practice facilitate such creative engagements?

REFERENCES

Abrams, D. (1997) The Spell of the Sensuous, New York: Vintage Books

Asker, D. (2018) The Art of Awareness: Motivations and Orientations in the Creative Arts, London: Austin Macauley Publishers

Asker, D. (2019) Dancing the Landscape, In Karen Bond (Ed). Dance and the Quality of Life, New York: Springer

Asker, D. (2020) Dear Heart, unpublished anthology of poetry and photographs

Behnke E.A. (2010) The Socially Shaped Body and the Critique of Corporeal Experience. In: Morris K.J. (Eds) Sartre on the Body: Philosophers in Depth. London: Palgrave Macmillan

Caldwell, C. (2012) Sensation, movement and emotion, In Sabine Koch, Thomas Fuchs, Michela Summa and Cornelia Muller (Eds) Body Memory, Metaphor and Movement pp. 253-265 Amsterdam: John Benjamin Publishing Company

Castaneda, C. (1969) The Teachings of Don Yuan: A Yaqui way of Knowledge, Berkeley: University of California Press

Etchells, T. timetchells.com accessed 17 February 2020

Geertz, C. (1973) The Interpretation of Cultures, New York: Basic Books Inc. Publishers

Healey, S. (2018) On View: Thinking Bodies, Dancing Minds exhibition April 12-28, 2018, Margaret Lawrence Gallery, VCA, Melbourne.

Kolter, A et al (2012) Body memory and the emergence of metaphor in movement and speech, In Sabine Koch, Thomas Fuchs, Michela Summa and Cornelia Muller (Eds) Body Memory, Metaphor and Movement pp203-226 Amsterdam: John Benjamin Publishing Company

Lakoff, G. and Johnson, M. (1980) Metaphors we live by, Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Lett, W. (2011) Making Sense of Our Lives, Eltham: Rebuss Press

Luhman, N. (2012) Theory of Society Volume 1, Stanford: Stanford University Press

Maturana, H. R. Varela F. G. and Uribe (1981) Autopoiesis: The Organisation of Living Systems, Its Characterisation and a Model, In Cybernetics Forum, Summer/Fall 1981, Vol X, No 2 and 3, pp 7-14, The American Society of Cybernetics

MacDowell, L. (2019) Instafame: Graffiti and Street Art in the Instagram Era, Chicago: Intellect, The University of Chicago Press

Mortiss, J. (2018) Divergent Dancing, performance installation, and unpublished doctoral thesis, Naarilla Studio, Kiah, NSW.

Richardson, L. (2005) Writing: A Method of Inquiry, In Norman Denzin and Yvonne Lincoln (Eds) The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, (pp. 959-978) Thousand Oaks: Sage

Rethorst, S. (2012) A Choreographic Mind: Autobiographical Writings, Helsinki: Theatre Academy Helsinki, Department of Dance, Kinesis 2

Shaughnessy, N. (2012) Applying Performance: Live Art, Socially Engaged Theatre and Affective Practice, Chippenham and Eastbourne: Palgrave and Macmillan

Sheets- Johnson, M. (2012) Kinesthetic memory, In Sabine Koch, Thomas Fuchs, Michela Summa and Cornelia Muller (Eds) Body Memory, Metaphor and Movement pp 4-73, Amsterdam: John Benjamin Publishing Company